The Wrong Problem

Why student loan forgiveness is a bad idea.

POLITICS

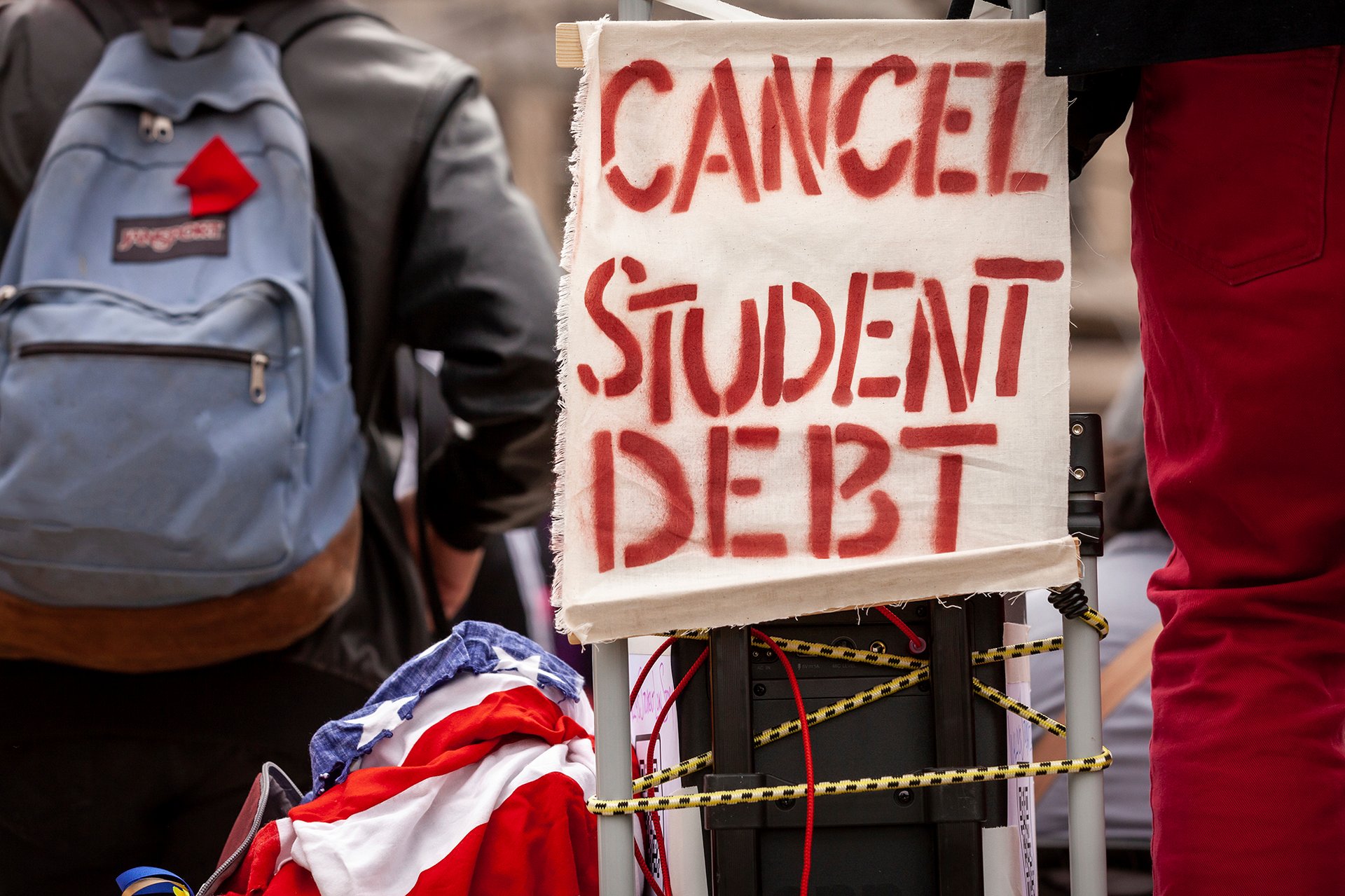

On February 28th, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments for and against President Biden’s student loan forgiveness policy. Chief Justice Roberts invoked the courts recently formulated “Major Questions” doctrine, a doctrine tailored from whole cloth and used to rationalize the judicial activism of the conservative majority (that will be the topic of the next blog post). But putting aside the legal authority for Biden’s attempts to forgive over $400 Billion in student loan debt, forgiving student loan debt this way is simply bad public policy. Essentially, it solves the wrong problem, and it makes the real problem even worse.

For example, let’s assume that the court rules that the forgiveness program is legal. What happens in ten or fifteen years? Education, after all, is getting more expensive not less, and student debt will continue to rise. Will there be another forgiveness program? Then another?

This predicament is like that revealed by Ronald Reagan’s amnesty for people who were in the country illegally in the 1980s. The Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 that he signed into law granted amnesty to about 3 million undocumented immigrants in the United States. As we can see today, however, that certainly did not solve the problem of undocumented immigrants. In fact, it probably made things worse, since amnesty gave the country the false impression that the problem was being addressed and allowed the problem to fester up until today, where there is simply no solution in sight.

To begin to solve the problem of unsustainable student debt from a public policy perspective, we first need to step back in time a bit to the first half of the last century. As the world moved into the modern era, it became clear that a quality education was the way to labor market success. In 1950, a high school diploma would land a graduate a solid, well paying, middle-class job. But in 2023, a high school diploma is an absolute minimum requirement to get nearly any job, and it is no longer enough to guarantee entry into the middle class. Why did this happen?

Over the last half century, the economic value of education has been driven by the increased demand for technical skills in digital technology, finance, and the sciences. The result is that the income gap between those with only a high school diploma or GED and those with more education is at an all-time high.

In addition, on-the-job training programs, once a mainstay of many businesses, are in decline. The set of skills required for many entry level jobs is more technical than ever and generally best acquired by formal education programs.

What the country now faces is the same challenges it faced in the last century: a good job and financial stability require free, universal access to quality education. The difference, of course, is the level of education required today versus fifty years ago. Just as the country decided, in the early 1900s, that the best way for students to get the quality education they needed to be successful was to provide free, universal education up to grade 12, the country must figure out how to make a four-year college degree free and universally accessible. That is the problem that needs to be solved. Forgiving student debt without solving that problem is simply too expensive and short-sighted.

Of course, college is not for everyone, and even if it is free, not everyone will avail themselves of the opportunity to attend college. That means that in addition to free college, the country needs to ensure that those whose interests lie more with learning a trade (e.g., plumber, electrician, mechanic), also have advanced educational opportunities. Again, just as some high schools offer dual tracks for college and learning a trade, state colleges can provide advanced education in the trades. There is, for example, a difference in the educational requirements to be an electrician versus a master electrician.

To summarize, the statistics are unequivocal, the road to a decent job and a decent lifestyle, in 2023, is best traveled with an education beyond a high school diploma. Not providing free (to students), universal education to a four-year degree simply guarantees the continuation of the status quo, a steadily increasing quality-of-life gap between the educational-haves and the educational-have-nots. Loan forgiveness isn’t going to fix that problem.

Of course, the TANSTAAFL principle does apply here, but it also applied to funding universal access to a high school diploma. The world has changed a lot since the early 1900s but access to the needed level of education to prosper has not. Instead of spending $400 billion on loan forgiveness, take that money and start the process of implementing free, universal access to a four-year college degree. That solves the right problem, not to mention, it is about time!

References:

Contact

Subscribe to my eNewsletter

© 2024. All rights reserved.

kellycunningham1021@gmail.com